Minnesota Farmers Make History by Obtaining the Nation’s First Organic Farming Research Grant

By Roger Blobaum

The attitude of big universities that grab all the agricultural research money and insist they should decide what needs to be investigated is stirring up some sharp competition from a group of organic farmers in Minnesota.

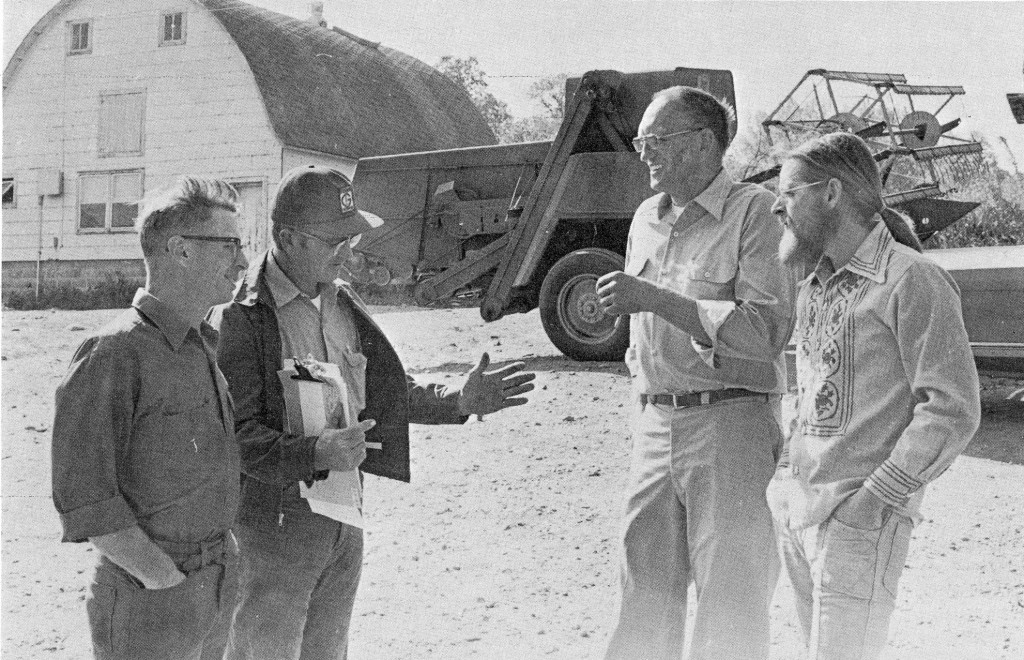

Lester Frohrip (left), president of the Soil Association of Minnesota, talks with board members Melvin Duntaman, Ardell Anderson and Larry Eggen

Six months after setting up the Soil Association of Minnesota, they had landed a research grant from the Minnesota Resources Committee and cemented a working relationship with scientists at Southwest Minnesota State, a college about 120 miles west of Minneapolis at Marshall.

The founding members adopted a constitution calling for action to promote natural farming, support research and legislation relating to ecological agriculture, and cultivate a social and fraternal spirit among environmental-minded farmers.

Unlike organic groups that emphasize marketing research, the want to document things like the feeding value of grain raised on organic farms and the impact of farm chemicals on soil productivity and water quality. Their plans include asking both foundations and the State Legislature for funding.

Heading the group is Lester Frohrip, a grain and livestock producer on 700 acres along the Minnesota River near Morgan. He graduated from the University of Minnesota’s College of Agriculture and sees through the cozy relationship chemical companies have built with land grant schools.

“The first thing we are trying to do is collect all the organic farming information that is available,” Frohrip explains. “Then we’ll decide what problems haven’t been looked at and determine the important and relevant research questions that we want to pursue.”

As a young farmer in the 1950s, he was one of the first in the neighborhood to apply anhydrous ammonia, getting good yield increases on most of his soils. But several things happened over the next 10 years, he recalls, that signaled trouble.

He reported upping fertilizer applications didn’t produce proportionately bigger yields (“apparently there are other limiting factors”), the soil seemed to be getting harder (“we needed a larger tractor to pull the same plow”), pigeon grass starting to become a serious problem (“we had to use chemicals to control it”), and the corn didn’t dry down in the fall like it had earlier (“that’s the reason for all the dryers today”).

Why was the organic matter content dropping in many soils, he asked himself, and why did corn produced naturally feed more hogs per bushel than higher-yielding corn raised with chemicals? He finally took his question to a private farm service laboratory and was sold on trying to farm again without chemicals.

“I don’t want to say that the answers are all there or that everything is going the way I want it to,” he admits. “But the start has been made and I can see that we are on the right track.”

Farming organically has convinced him agricultural colleges have gone off on a tangent in promoting chemical methods that damage the soil, pollute the water, and lead to more serious weed and insect problems than farmers had before.

Frohrip also is keenly interested in the nutritional aspects of naturally grown food. He and his wife have a small health food store in their home and a facility for stone grinding flour and cleaning and bagging grain is under construction on the farm.

Although the Soil Association’s first grant totals only $3,500, it is considered a highly significant breakthrough. The funding covers a study of the runoff of nitrates and phosphates from farms using both organic and chemical practices. Scientists will examine farm runoff discharges through tile lines and attempt to determine its effect on farm wells in the area.

The Future Farmers of America (FFA) chapter at Westbrook, Minn., has tested dozens of shallow wells in the southwest part of the state and found unsatisfactory nitrate levels in most of them. It is assumed that nitrogen fertilizer contributes to the high nitrate level.

Members of the association have found a warm welcome at Southwest State. Profs. Lester Schmidt and Charles Reinhart helped organize the group and shape its initial research proposal. Robert Eliason and Leo Bowman, who are doing the water runoff study, also are faculty members.

Several students have become involved. A recent issue of the association’s newsletter reports that a student is preparing a term paper on a new method of making micro-biological evaluations of soil fertility.

The working relationship is in sharp contrast to the way organic farmers were treated recently at nearby Brookings, where South Dakota State University rejected their study proposal. It was designed to examine the quality and quantity of feed grown under organic management practices as compared to standard practices in a given area.

SDSU scientists would agree only to a one-year study comparing the yield of crops produced by the two methods. The proposal had called for growing grain on plots over a 5-year period, feeding it to livestock, and documenting the growth and health of the animals.

The turndown might have been expected. South Dakota State exposed its hand earlier in a report for the Cooperative Extension Service entitled “Facts About Organic Farming and Gardening.” This attack was supported by such flimsy evidence as the result of a one-year “experiment” by the Geneva (Neb.) Young Farmers Association.

It’s possible, Frohrip reports, that the South Dakota proposal may be accepted at Southwest State, which indicated an interest in doing it on some land under cultivation near the campus. One drawback is lack of funds for a structure to house livestock involved in the experiment.

Marketing activities of the association probably will focus on adopting standards and paving the way for certification. “We’re willing to put on paper how our grains and livestock are produced,” Ardell Anderson of Walnut Grove, Minn., reports. He is a director of the Soil Association and specializes in producing food for allergenics.

Some idea of the challenge accepted by members of the Minnesota group is seen in recent remarks by John Enestvedt of Sacred Heart, who is active in both the Soil Association and a regional group called the Organic Growers and Buyers Association.

Organic farmers have to find ways to adopt garden practices like composting, animal and poultry manuring, and mulching, he points out, even though they have to handle hundreds of acres of land. They need to know more about green manuring, mulch tillage, and other organic procedures to fit these larger acreages, he continues, and remember at the same time to help expand knowledge about organic gardening.

“Most farmers growing crops organically cannot depend on covering their cropland sufficiently with compost, animal and poultry manure, or by mulching,” Enestvedt adds.

“So they have to look at the other side of the organic growing coin because it is only through understanding of the soil that we are going to clean up our farmland and be able to grow enough food without the use of chemicals.”

Roger Blobaum interviewed and photographed and wrote about organic farmers in the Midwest in the early 1970s. These organic farmer profiles were initially published during that period in Organic Gardening and Farming magazine or in the Organic Observer. Most were published again later in two Rodale Press publications, the Organic Farming Yearbook of Agriculture published in 1975 and Organic Farming: Yesterday’s and Tomorrow’s Agriculture published in 1977.