Presentation: A Brief History of the Organic Farming Movement in the Midwest in the 1970s

Who These Early Organic Farmers Were, The  Barriers They Had to Overcome, and How They Built the Movement Together

Barriers They Had to Overcome, and How They Built the Movement Together

A workshop at the 2011 MOSES Organic Farming Conference by Roger Blobaum, (February 2011)

“When I was invited to present a workshop on the history of organic farming, the workshop coordinator and I agreed that the history was too large a topic to cover in one workshop session. The result was a presentation limited to the history of organic farming in the Midwest in the 1970s.” — Roger Blobaum

Focus on the 1970s: 1) It was a period when farmers in the Midwest made real progress in working together and in shaping and expanding the organic farming sector and 2) It was a period when I had the opportunity to be involved as a writer, a photographer, a researcher, and an advocate.

This presentation reflects my own intense interest in organic agriculture, the friendship of organic farmers who provided lots of inspiration and information as I wrote about their concerns and their successes, and my strong interest in identifying and dealing with the  barriers organic farmers had to overcome.

barriers organic farmers had to overcome.

Important in this period was the way organic farmers and consumers cooperated in developing standards and establishing third-party certification.

I came across organic farming by chance.

At a board meeting of Iowans for Environmental Quality in 1971, a colleague announced that he planned to visit an organic farm after the meeting and wondered if anyone wanted to go along. Although I had covered farm stories as a reporter and had worked on the bill to ban DDT and other farm and environmental bills as a Congressional staffer, the term “organic farming” was entirely new to me. I decided I needed to find out what this was all about.

We arrived at Clarence Van Sant’s farm near Grinnell late on a sunny September afternoon. It looked like a typical Iowa farm when we drove in. After greeting us, Clarence picked up a shovel and led us out to the edge of a corn field. He stopped, turned over a few shovels of rich black soil, and watched our reaction as dozens of earthworms came tumbling out. I knew immediately this was something special.

We continued to be impressed as we walked past a field of weed-free soybeans, crossed timothy and red clover hay ground that was part of his crop rotation, and admired his beautiful Charola is cattle.

is cattle.

Clarence told us there were quite a few organic farmers in the Midwest, that they had livestock and rotated their crops, and that they were doing well. He said most raised all of their own feed, many purchased organic fertilizers and soil conditioners, and some were selling direct to consumers.

We asked where farmers got their organic farming information. The most important source, he said, was other organic farmers. He said some information was available from small companies selling organic fertilizer and other inputs. He also cited the Rodale Press and its national magazine, Organic Gardening and Farming.

He didn’t have anything good to say about USDA or land grant universities or Extension. He said they were biased, looked down on organic farmers, ignored their need for research, and refused to acknowledge their accomplishments.

I was so moved by this experience that I drove to Emmaus, Pennsylvania, and paid the Rodale Press a visit. The editors of Organic Gardening and Farming magazine proudly reported the circulation of the magazine had reached 800,000, that they had published a national organic directory, and that they were promoting organic farming around the country. They estimated there were at least 10,000 organic farmers nationwide.

I was so moved by this experience that I drove to Emmaus, Pennsylvania, and paid the Rodale Press a visit. The editors of Organic Gardening and Farming magazine proudly reported the circulation of the magazine had reached 800,000, that they had published a national organic directory, and that they were promoting organic farming around the country. They estimated there were at least 10,000 organic farmers nationwide.

The national organic directory, published in 1971, provided the only systematic overview of the organic farming community available at that time. It included a national listing of more than 1,600 growers, distributors, health food stores, and other sources of organic food. It also included listings for more than 500 ecology action groups, more than 200 sources of natural fertilizers, soil conditions, and mulching materials, and more than 100 Rodale-organized organic gardening clubs.

The magazine had Floyd Allen working as West Coast editor. He also helped lead th e Rodale organization’s unsuccessful attempt to become an organic certifier in California. Another editor involved in this effort returned home and described organic certification as “a can of worms.” After the Rodale Press gave up on this, it helped fund a group of organic growers who organized what is now California Certified Organic Farmers (CCOF).

e Rodale organization’s unsuccessful attempt to become an organic certifier in California. Another editor involved in this effort returned home and described organic certification as “a can of worms.” After the Rodale Press gave up on this, it helped fund a group of organic growers who organized what is now California Certified Organic Farmers (CCOF).

The editors also were working on “The New Food Chain,” a book aimed a bringing organic farmers and consumers together to challenge the industrialization of agriculture.

The book cited a survey that showed 36 percent of Americans said they were convinced that food is no longer safe. And it called for sweeping aside artificial barriers that were making it difficult for farmers and consumers to work together.

I was impressed, as I had been with Clarence and his organic farm, and signed up with the Rodale Press to gather and report information on organic farming in the Midwest. My goal was to use the funds provided to visit 50 organic farms. But shortly after returning home, an editor called and asked me to interview and photograph Ralph Engleken, an organic farmer in northeast Iowa, and send in a story.

I want to introduce you to Ralph and several other outstanding organic farmers I interviewed and wrote about over the next two or three years. These stories describe the culture of organic farming, the values these farmers shared, their concerns about chemical farming, and the accomplishments that made them so special.

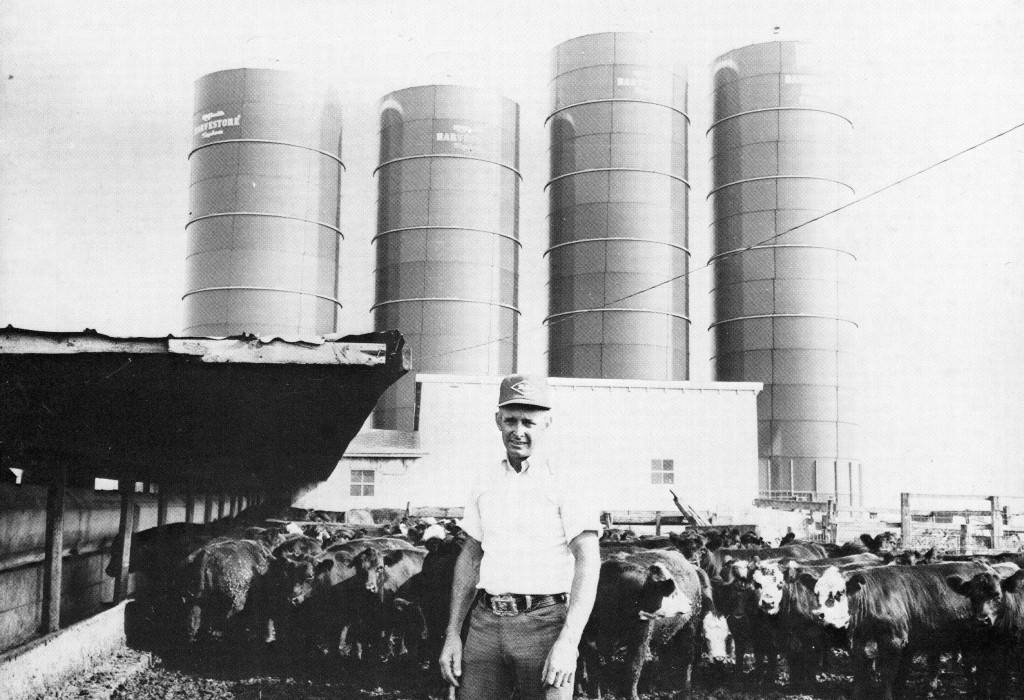

The Engleken’s 700-acre organic operation with its 145 bushels per acre corn yield, well above the county average, and its four-year corn-oats-hay rotation, was impressive. Heavy applications of livestock manure needed to produce good crops came from 200 stock cows plus an additional 300 calves purchased each year to feed out along with 400 hogs.

But what stood out was Ralph and Rita’s story about why they had switched to organic 14 years earlier. It was a story much like those I heard over and over from organic farmers in the 1970s.

“The whole family was sick all the time . . . skin

rashes, fever,” Ralph reported. “We finally traced it to the clothes I’d been wearing when I was spraying on chemicals. We had just moved to this farm when we found that out and we’ve been farming it organically ever since.”

I returned to Clarence’s farm to do a story for the magazine and found his direct sales to consumers had been so successful that he had purchased a building and opened Van’s Health Foods near the Grinnell College campus. Customers he had been supplying for years with organic pork, or had been on his fresh egg route in town, helped make it an immediate success.

“A lot of people object to organic foods because the price is too high,” he explained. “But if you can sell direct from the farm to the consumer, there isn’t anybody going to beat you on price.”

It was highly unusual to find organic farmers who were close neighbors. But that was the case with Del Akerlund, K.C. Livermore, and Ralph Rolfs who had adjoining crop and livestock operations near Fremont, Nebraska, and farmed a total of 1,300 acres.

Livermore admits he was a little skeptical about switching to organic.

“But every year it got better, and my fourth year was the big turning point. We had better crops, we had fewer weeds, and we had easier farming. It was just wonderful to be able to farm that way again.”

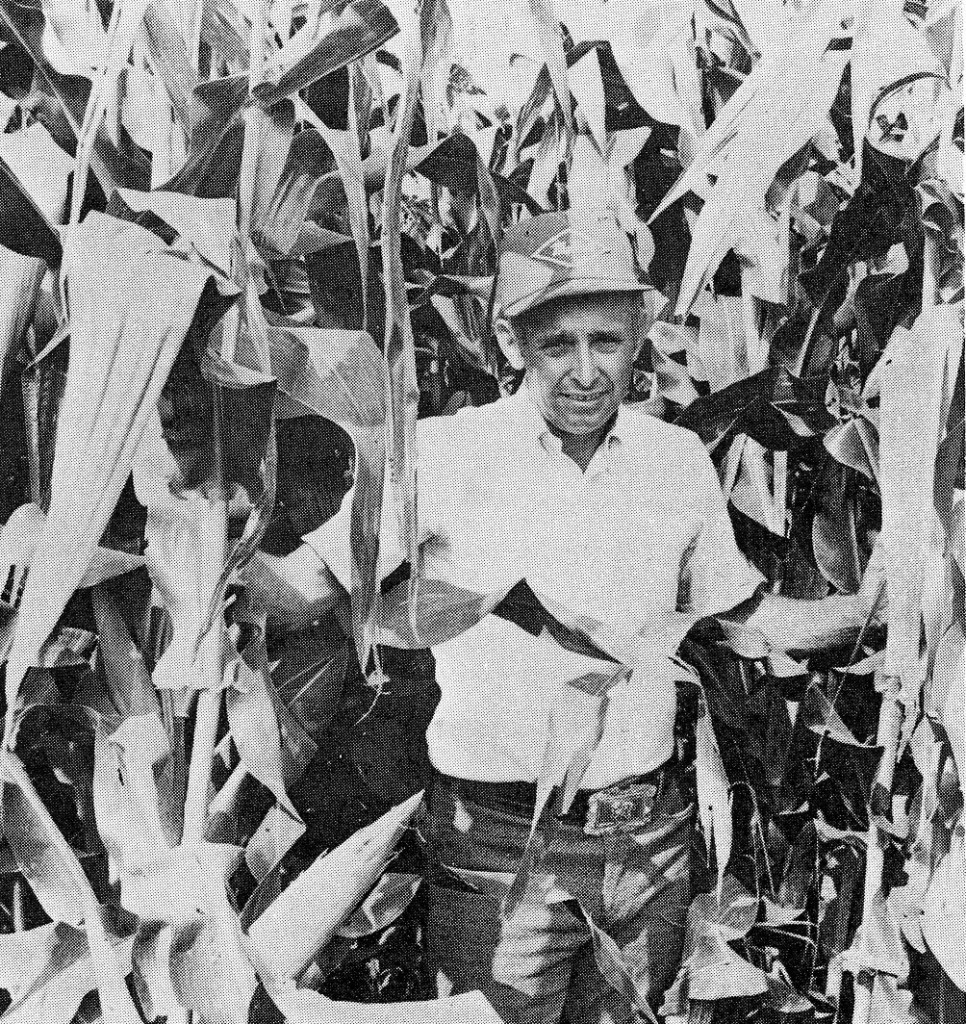

K.C. Livermore’s drought-proofed cornfield

In the summer of 1974 the worst drought since the Dust Bowl days hit eastern Nebraska and ruined the crops of conventional farmers, even those who irrigated. But Akerlund, Livermore, and Rolfs had good crops due to the way organic practices had increased the water-holding capacity of their soil and drought proofed their farms.

They also shared the Nebraska Wildlife Federation’s first Conservation Award of the Year for improving habitat for quail and pheasants and other birds they credited with protecting their crops from insect damage.

“On the last round when we were combining oats,” Akerlund reported, “there were about 200 pheasants running ahead of the combine and we had to stop several times to let them get out of the way.”

Akerlund also talked about his continuing effort to get the University of Nebraska to conduct some organic farming research. I learned later that the assistant director of the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station at Mead, after spending an afternoon on Del’s farm, established the first Midwest research plots comparing the performance of organic and conventional farming. These experimental plots, start ed 35 years ago, continue to document the benefits of farming organically.

ed 35 years ago, continue to document the benefits of farming organically.

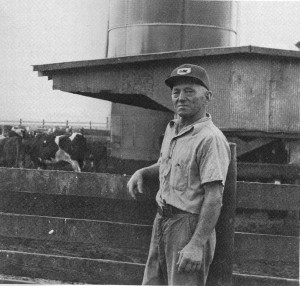

Walter and Oscar Hobbie lived a mile apart on organic farms near Flandreau, South Dakota, and dairy cattle, beef cattle, and hogs consumed all the feed produced on their 1,100-acre operation. Their large livestock operation also produced lots of manure to fertilize their fields. Like so many organic farmers, the first thing they noticed after switching to organic was greatly improved livestock health.

“Our veterinary thought we had switched vets,” Walter recalled, “because he didn’t have to come out anymore like he used to.”

Ray Juhl, who farmed 2,500 acres near Middle River, Minnesota, saw production of organically grown grain and stone-milled flour as an emerging industry with strong growth potential. He started out turning out small bags of flour under a “Natural Way Mill” label for health food stores. By the mid-1970s he had one of the nation’s largest on-farm milling setups.

“No-one has ever shown this kind of interest in anything we’ve ever done before,” he reported. “All I know is that the visitors, the mail, and the phone calls would indicate nearly everybody wants some.”

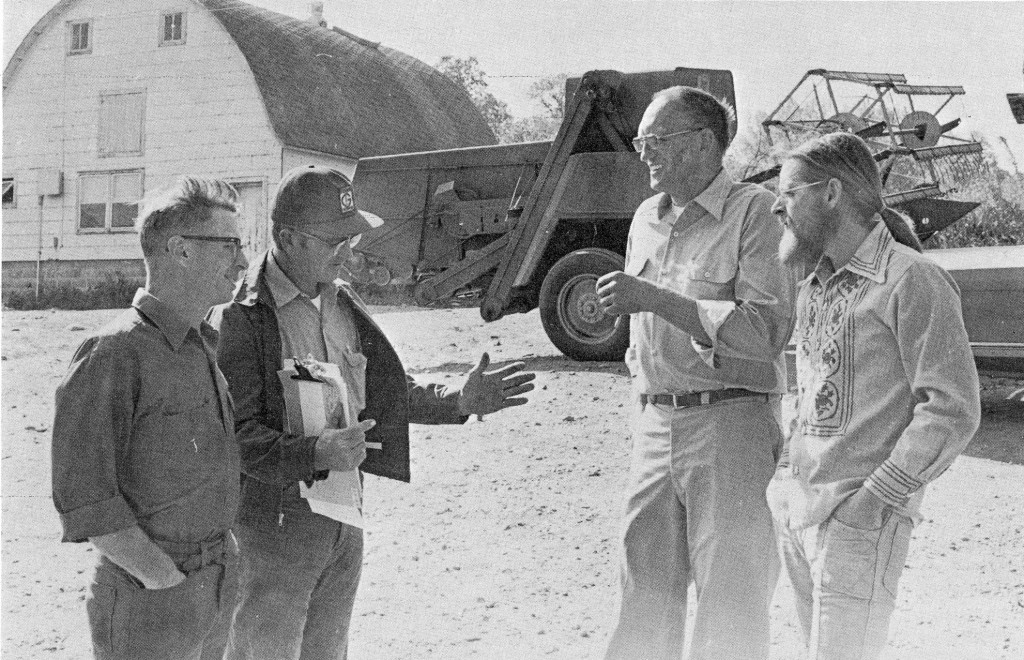

Lester Frohrip (left), president of the Soil Association of Minnesota, talks with board members Melvin Duntaman, Ardell Anderson and Larry Eggen

Finally, several Minnesota organic farmers decided to do something to challenge the land grant universities that were grabbing all of the agricultural research money. Six months after setting up the Soil Association of Minnesota, they landed a research grant from the Minnesota Resources Committee. The $3,500 grant funded a study comparing tile line discharges on organic and conventional farms to determine whether nitrogen fertilizer applications were causing high nitrate levels in farm wells.

The founding members also established this new organization to address related issues like the fact that higher fertilizer applications didn’t produce proportionately higher yields, that soil organic matter was dropping, that the soil was getting harder and more difficult to work, that pigeon grass had become a serious problem, and that corn didn’t dry down in the fall like it had earlier.

By the middle of the 1970s, new developments made organic farming information more avail able. The Rodale Press published the “Organic Farming Yearbook of Agriculture” in 1975. Two years later it published “Organic Farming: Yesterday’s and Tomorrow’s Agriculture,” a 340-page book packed with organic farming information.

able. The Rodale Press published the “Organic Farming Yearbook of Agriculture” in 1975. Two years later it published “Organic Farming: Yesterday’s and Tomorrow’s Agriculture,” a 340-page book packed with organic farming information.

The Rodale Press also launched The New Farm, a magazine that focused on organic and sustainable agriculture. Most of the organic farming content that had been carried in Organic Gardening and Farming magazine, as a result, was carried instead in the new publication. Chuck Walters, who launched Acres USA in 1971, had built this publication into an important source of organic farming information and had built a following for the annual Acres conferences.

Organic Farmers Also Were Organizing

The Minnesota Soil Association and the South Dakota Soil Association began convening  meetings and publishing newsletters. Midwest Organic Producers Association, organized a short time later to promote organic farming, launched a newsletter serving members of organic farming groups in Minnesota, South Dakota, Kansas, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Nebraska.

meetings and publishing newsletters. Midwest Organic Producers Association, organized a short time later to promote organic farming, launched a newsletter serving members of organic farming groups in Minnesota, South Dakota, Kansas, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, and Nebraska.

Although the problems and experiences of organic farmers were receiving more attention, no attempt had been made to ask them directly how they were doing overall. The first attempt, a Center for Rural Affairs survey of 147 organic farmers in Nebraska, produced these findings:

–Contrary to the belief that organic farmers did well financially only because they sold their products to health food stores at high prices, the survey showed most of themn sold their grain and livestock the same places their chemical neighbors did. But with lower input costs and comparable yields, thkey were able to realize a greater net profit.

–Some of the survey respondents reported their yields with organically-grown crops were better than the yields they had before switching to organic. This was especially true for soybeans, oats, alfalfa, and wheat.

–Many of the respondents reported that livestock preferred the grain they produced on organic farms, that livestock were healthier when fed hay and grain produced organically, that they seldom needed the services of a veterinarian, and that the feed value of grain produced on organic farms was superior.

The survey reported concluded that most farmers switched because they were concerned about the disappearance of wildlife on their farms, about soil that lacked life and had become hard and difficult to work, about livestock health problems, and about the adverse impact of chemical residues on their families and their livestock.

Organic Input Suppliers

Another important develop in the Midwest during this period was the growing number of small companies that sold foliar sprays, soil conditioners, bulk and bagged compost, granite dust, and similar products to organic farmers. As noted earlier, the Rodale Organic Directory published in 1970 included a state-by-state listing of more than 200 of these small input suppliers.

Some, like Hy-Brid Sales Company in Council Bluffs, Iowa, marketed multi-year “programs” to transitioning organic farmers that included soil tests processed at private labs and the fertilizer and soil conditioners and other products that these tests called for. The company, started by Bill Graves more than 50 years ago, provided information and organic inputs to many of the farmers who switched to organic in Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas.

These companies brought farmers together at dinner meetings in the winter months to provide information to farmers thinking about switching to organic and to market their products. Many organic farmers met and shared information at these meetings.

These events also provided company representatives opportunities to push back against conventional fertilizer companies pressing state regulators to prohibit the sale of organic fertilizers. And against Extension Service agents who put out press releases slamming these and similar organic inputs as a waste of money. My own files show many organic farmers at that time were applying Agriserum, Wonder Life Trace Minerals, Clod Buster, Sur-Gro, Microlite, Calphos, granite dust, kelp and fish foliar fertilizers, and similar products.

Organic Bashing

Although organic farmers consistently had comparable yields and did well financially, they had difficulty countering claims that they were little more than throwbacks to the past. Many of these outrageous claims were made by people at USDA.

Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz began the 1970s, for example, with a statement that reflected his strong bias against organic farmers. “Before we go back to an organic agriculture in this country,” he told a network news interviewer, “somebody must decide which 50 million Americans we are going to let starve or go hungry.” Later Deputy Secretary John White claimed manure piles as high as the Empire State Building would be needed to make organic farming work.

Positive Organic Media

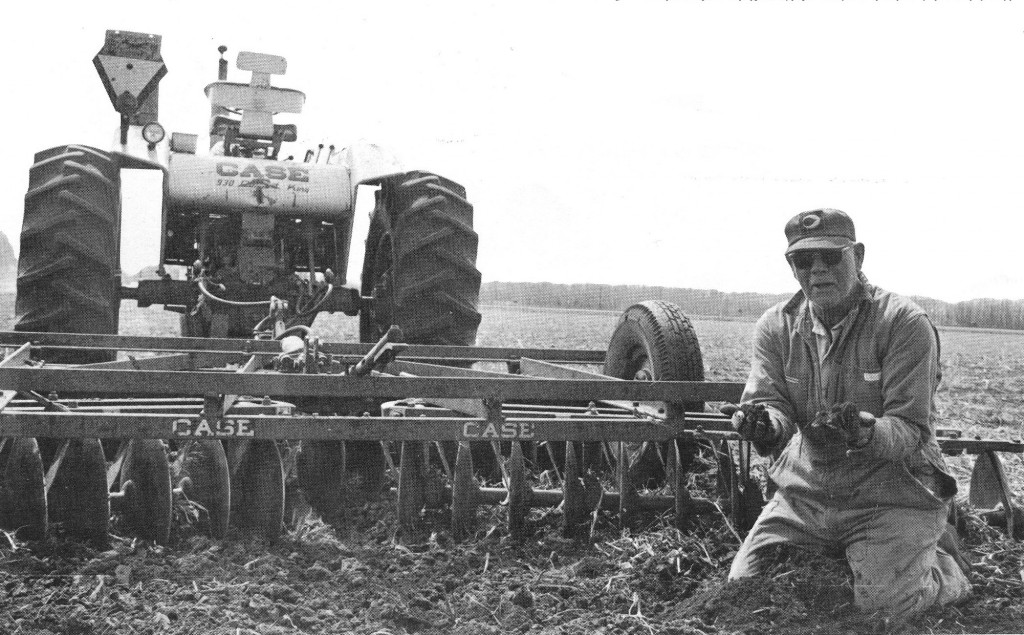

But some unexpected good news about organic farming several years later put these critics on the defensive. But and other organic farming bashers were stunned on July 20, 1975, when they opened their Sunday New York Times and saw a long front page story headlined “Organic Farms Found Efficient.” It was illustrated by a photo of an Iowa farmer in a large field of organically-grown corn.

The story reported on a Washington University study that concluded that farming organically is a viable economic alternative for commercial-size crop and livestock farms in the Midwest. Data collected during a 3-year period from 14 matched sets of conventional and organic farms showed that organic farms had somewhat lower crop sales per acre of cropland, that conventional farms had higher purchased input costs, that organic farms had somewhat higher labor requirements, and that farmers in both groups made about the same amount of money. A surprising and important difference was that the conventional farmers used more than twice as much energy.

Organic farming critics were really upset when a report on this research was published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, a respected peer-reviewed journal. Several leading newspapers, including the Des Moines Register, also weighed in with editorials criticizing USDA and the land grant institutions for emphasizing farm chemicals while paying little attention to their environmental and human health consequences. Even Science, one of the nation’s most prestigious journals, gave the Washington University study a favorable review.

Organic Survey and Benefits

Another result of these positive developments was increased public interest in what motivated organic farmers. A Washington University team responded with a survey of more than 300 organic farmers who farmed 100 acres or more in Minnesota, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and Illinois. It showed they were not “back to the landers” with small marginal operations farmed with horses as many critics had claimed.

“The reasons for choosing organic methods generally were practical and related to such specific problems with conventional farming as possible adverse health effects of pesticides. Ideological or philosophical considerations also played a lesser role,” the survey showed. “But choosing to use organic methods does not necessarily set organic farmers apart in a fundamental way from the conventional farmers who are their neighbors.”

The top five reported advantages of switching to organic farming were healthier for the farmer and his family, healthier for livestock, more in harmony with nature, better for the soil, and better for the environment.

Other studies and surveys late in the 1970s confirmed this information and helped lay the groundwork for the really big development that came at the end of the 1970s. That was the request to a team of USDA scientists from Secretary of Agriculture Bob Bergland, to conduct a study of organic farming. Bergland, a Minnesota farmer before becoming involved in politics, had a neighbor who was a successful organic farmer and did not like the way organic farmers were disrespected at USDA

A USDA press release on June 19, 1979, reported that Anson Bertrand, the head of USDA’s Science and Education Administration, had put together a Coordinating Team for Organic Farming to study the benefits of organic farming. He noted that many conventional farmers questioned whether organic farming could produce enough food to feed the millions of people who must be fed in modern times.

“Has new knowledge already boosted the productive power of organic farming?, he asked. “We’ll find out. When the facts are in, we’ll use them to develop a program or policy recommendations for Secretary Bergland. If it appears reasonable to do so, we may suggest additional redirection of USDA research, education, and funding.”

And that’s exactly what happened a few months later when USDA published the famous 1980 Report and Recommendations on Organic Farming. It estimated that there were at least 20,000 organic farmers in this country and concluded that the full range of research and education programs should be developed to address their needs and problems.

This unexpected and highly significant development, endorsed by the nation’s secretary of agriculture, showed how far organic farmers had come in 10 years in gaining respect and acknowledgment for their many achievements. It provided a most fitting conclusion to the history of organic farming in the Midwest in the 1970s.