‘Every Year Was Better; The Fourth Was the Turning Point. It Was Just Wonderful To Be Able to Farm That Way Again’

by Roger Blobaum

If you’re wondering whether large family-type farmers can kick the chemical habit and still grow plenty of food profitably, you should see the three organic operations just north of State 33 near Fremont in eastern Nebraska.

These up-to-date farms cover more than 1,300 acres of some of the most productive land on the Platte River. They have been farmed without chemicals since the late 1960s by Ralf Rolfs, Del and Van Akerlund, and K.C. Livermore.

In addition to producing good crops, they save energy. Less gasoline and diesel fuel are needed to power tractors in fields that work easier and less propane is needed to dry corn artificially. Besides that, there’s the natural gas that isn’t used to manufacture anhydrous ammonia and other agricultural chemicals for these farms.

Any doubts these farmers had when they decided to make this abrupt switch (all admit they had some) are forgotten. They are anxious to share their experiences and have the kind of enthusiasm that even a farm chemical salesman would find hard to resist.

Important in these operations is a four-year crop rotation that includes two years of corn, one of soybeans, and one of oats with a legume such as sweet clover or hairy vetch. The soybeans and legume crops “fix” nitrogen from the air, adding this natural plant food to the soil, and the legumes also provide green manure to be turned under.

Rotating crops also prevents a buildup of corn rootworms, borers, and other pests that cause serious problems for farmers who do continuous cropping and rely on chemicals to control pests.

All three farmers have some difficulty finding organic markets for their grain and livestock. They have discovered, however, that they get good yields consistently and don’t need special organic outlets or premiums to operate profitably.

Both Rolfs and the Akerlunds have sold corn to a Primrose, Nebraska, cattle feeder who produces organic beef. The Akerlunds usually buy calves to feed out. But their lots are empty now due to low beef prices.

Livermore has a steady list of customers who place orders for the 40 to 50 calves he fattens each year on organically-grown grain. He has stock cows to provide calves for this part of his operation and to utilize roughage on the farm. He also has some sheep.

The economics of farming without chemicals is an eye-opener. While corn farmers spend up to $50 an acre for chemicals, and sometimes even more, it requires only a fraction of that for an organic farmer’s purchased inputs.

Livermore reports his per acre costs since he quit chemicals have averaged about $8 a year. That covers soil conditioners and additives and a liquid fish fertilizer. He also has manure from his livestock operation to spread on the land.

“The first year we dropped chemicals we lost 10 to 15 bushels an acre in yield, but we didn’t have that $30 an acre for fertilizer against it that we had before so we actually were money ahead,” he recalls. “Each year without chemicals our crops get better, and today we are outdoing our chemical neighbors.”

Livermore’s soybeans yielded more than 50 bushels an acre in 1973 while adjacent fields, given the full chemical treatment, were weed infested and yielded only about half as much.

Rolfs said he never spends more than $10-12 an acre for purchased natural products on his cropland.

“I was up to nearly $40 an acre on commercial fertilizer before, at prices that were much lower than they are today,” he reports. “I can’t see where farmers are going to even get back what they are spending for fertilizer now. It’s a hopeless situation.”

He said the biggest corn crop he had on his home 80, using the full range of farm chemicals, was 130 bushels per acre. In 1973 with less than $12 an acre spent for natural fertilizers, he said, his corn on the same land averaged 120 bushels.

How about weeds? Can a farmer get along without herbicides when weeds are a constant problem even to those who use all the latest chemical weed killers?

Livermore says commercial fertilizers feed the weeds as well as the crops and reports his fields and those farmed by Rolfs and the Ajkerlunds are cleaner than those of their neighbors who use weed killers.

“We don’t have the weed problems we had when we were using chemicals,” he declares. “When we dropped chemicals, we found the weeds didn’t grow as fast as the crops did. And so, with our power equipment and the speed we have on tractors, it isn’t hard to control weeds without chemicals.

The message is that it pays to be a good farmer, killing weeds with good practices rather than trying to poison them.

“I like to go over the corn twice with a rotary hoe, and then twice with a rolling cultivator,” Del Akerlund says.

“Sometimes we have to use a sweep-type cultivator if we get a little behind in our work. But we prefer not to use the sweep because it will weave in the row, whereas the rolling cultivator goes perfectly straight.”

How about the energy savings and its implications for the future of American agriculture?

Akerlund points out that experience on their 760-acre farm shows they have been able to cut back in terms of power requirements.

“Our tractors are smaller than what we used to have,” he notes. “Better tilth in the soil makes easier pulling, and we are not using the fuel we used to.”

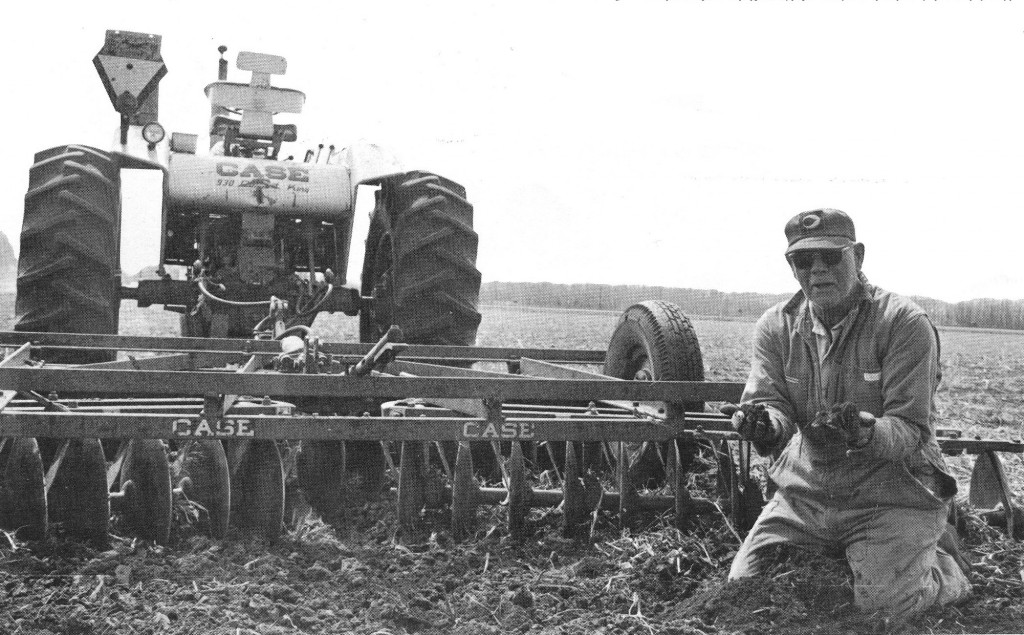

Livermore said his ground farms easier than it used to, and Rolfs has had a similar experience. Pointing to the chisel plow he has been using the past 12 years, he continues, “The first year I had that I tried to pull it in third gear. Now I can pull it in fifth.”

Although the Akerlunds still dry corn in the fall, they bring it down to only 15 percent moisture. A lot of people, Del Akerlund says, contend you can’t keep that kind of corn in large bins for long periods of time.

“But this year we have 9,000 bushels of shelled corn in one bin and all we have there is a seven-horse aeration fan,” he reports. “If you go up there today you can smell the sweetness of the grain.”

Akerlund feels more should be done to develop corn that ripens in the field so farmers won’t have to invest in drying equipment and pay high prices for propane.

“If things were done right as far as improving varieties is concerned,” he observes, “we could have corn that would ripen naturally and that wouldn’t have to be dried.”

Livermore picks his corn instead of combining it in the field and ends up with several thousand bushels of ear corn. He doesn’t have any drying equipment and says he feeds livestock from the crib year-around without any spoilage.

Organic farmers like to talk about their soil and to pick it up by the handfuls, smell it, and lovingly run it through their fingers.

“Without chemicals there’s a decided difference in how mellow the soil is. We don’t have any cloddy soil like we used to,” Livermore explains. “And we don’t have the green streaks in the field after a rain. We actually saw moss on the top of the ground at times when we used chemicals. We don”t see that any more.”

“We’re putting on some gypsum to lower the magnesium, and we’re putting on 550 to 600 pounds per acre of natural product, a blend of soft colloidal phosphate with a small amount of granite dust and some trace elements,” Akerlund reports. “This is probably good for three years and will keep our ground in good condition.”

All three of these farmers decided to drop chemicals after visiting some organic farms in Iowa. Livermore admits he was a little skeptical.

“But every year it got better, and my fourth year was the big turning point,” he recalls. “We had better crops, we had fewer weeds, and we had easier farming. It was just wonderful to be able to farm that way again.”

Roger Blobaum interviewed and photographed and wrote about organic farmers in the Midwest in the early 1970s. These organic farmer profiles were initially published during that period in Organic Gardening and Farming magazine or in the Organic Observer. Most were published again later in two Rodale Press publications, the Organic Farming Yearbook of Agriculture published in 1975 and Organic Farming: Yesterday’s and Tomorrow’s Agriculture published in 1977.