Article published in “The Environmental Magazine” – Eating As If the Earth Mattered 1992

The Environmental Magazine | Eating As If the Earth Mattered

Click for pdf file: January/February 1992 | Eating as if the Earth Mattered

By Roger Blobaum and Lisa Lefferts

By Roger Blobaum and Lisa Lefferts

January/February 1992

Environmentally savvy consumers steer clear of toxic cleaners, bleached coffee filters and plastic bags at the supermarket, and fret about the recyclability of containers. But most of us barely give the environment a second thought when it comes to choosing food, the product we buy most often at the grocery store. But besides profoundly affecting our health, our food choices greatly affect the environment.

When shopping for food, if we’re thinking about anything other than appearance or price, we’re probably thinking about how our food choices affect our health. The link between diet and health is hard to ignore, what with the Surgeon General, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and American Heart Association, to name a few, all agreeing we should be eating fewer fatty foods and more complex carbohydrates like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

Unfortunately many shoppers who see themselves as “green” consumers and know all about rain forest destruction and recycling have been slow to catch on. Expanding these “green” concerns to the entire food system, including the farms where food is grown, would help make agriculture much more Earth friendly.

How this connection can be missed was illustrated recently when an organic farmer approached an environmental leader and asked for help in organizing a sustainable agriculture event. “We have all we can handle with environmental problems,” the environmentalist responded. “We don’t do agriculture.”

This kind of response overlooks the damaging impact of many conventional farming practices on the environment. Agriculture’s addiction to pesticides, fossil fuel energy and other resource-depleting inputs and practices is, to say the least, a serious environmental threat.

The Chemical Feast

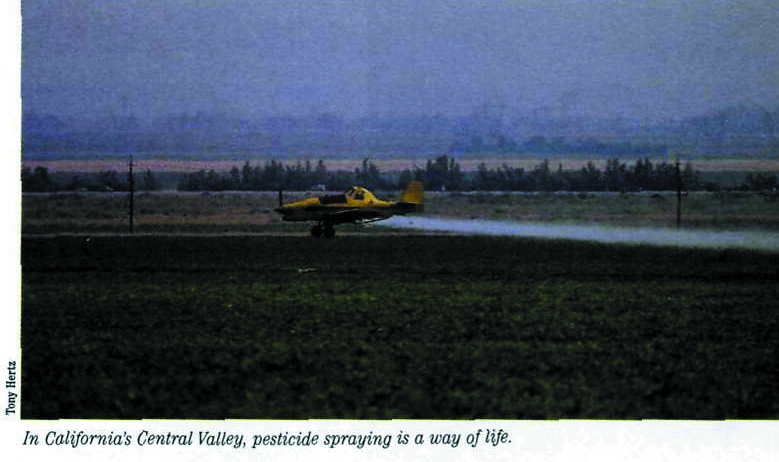

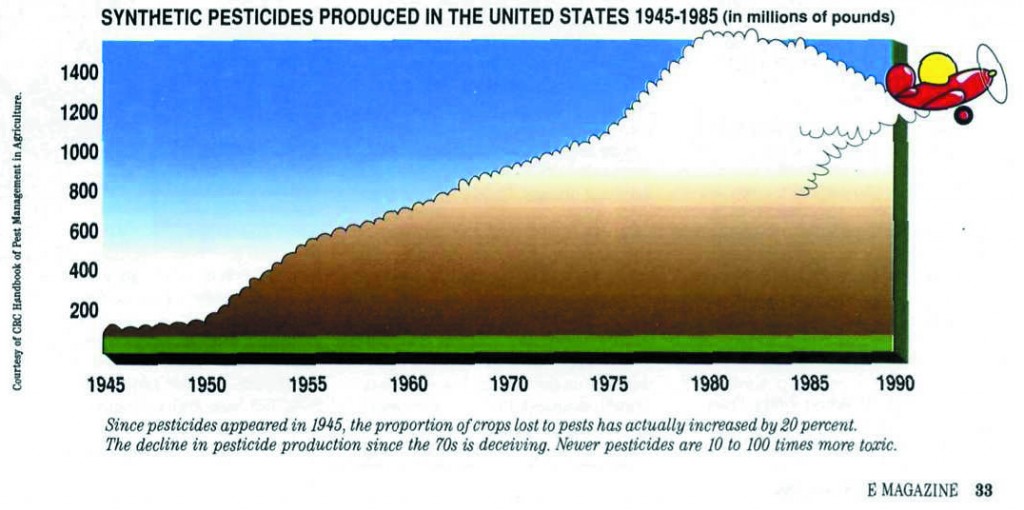

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), farmers now use 845 million pounds of pesticides annually. Chemical companies churn out more and more pesticides as pests develop resistance, leading many to question the role that pesticides play in agriculture. The NAS noted in 1986 that there were no longer any effective chemical pesticides to control some major crop pests in some areas.

With so many pesticides being used, you’d think the pests would all be wiped out by now. But David Pimental, a Cornell University agricultural scientist and author of a series of pesticide use studies, reports that the proportion of crops lost to pests has increased nearly 20 percent since chemical pesticides came on the scene around 1945. He has also calculated that the indirect costs of pesticide use—including human poisoning, harm to fish and wildlife, livestock losses, groundwater contamination, and destruction of natural vegetation–add up to at least $955 million per year. Adding in the costs of unrecorded losses of fish, wildlife, crops and trees, monitoring food and water for pesticides, and chronic health problems such as cancer would bring the total closer to $2 to $4 billion. Of course, it’s not really possible to put a price tag on a human life or a contaminated environment.

pesticides came on the scene around 1945. He has also calculated that the indirect costs of pesticide use—including human poisoning, harm to fish and wildlife, livestock losses, groundwater contamination, and destruction of natural vegetation–add up to at least $955 million per year. Adding in the costs of unrecorded losses of fish, wildlife, crops and trees, monitoring food and water for pesticides, and chronic health problems such as cancer would bring the total closer to $2 to $4 billion. Of course, it’s not really possible to put a price tag on a human life or a contaminated environment.

The chemical assault on farmland is so great that pesticides and nitrates from synthetic fertilizers have shown up in groundwater in 26 states. The EPA also reports that farming is the largest non-point source surface water polluter. Monoculture, the year-after-year cropping of the same fields with the same crop (made possible by pesticides) leaves soil exposed and contributes heavily to an estimated one billion tons of eroded soils washed into waterways each year with devastating impact on many lakes, rivers, and bays.

A dramatic new link between chemical farming and environmental degradation made headlines early in 1991. “It’s raining Lasso” was the lead of a Des Moines Register story describing how April showers in Iowa contained alachlor, an herbicide commonly known as Lasso, and other agricultural chemicals.

The story described a U.S. Geological Survey report on the farm chemical content of rain in 23 Midwest and Northeast states. It showed that pesticides sprayed and spread on farm fields evaporate and return to Earth in spring and summer rains. Earlier studies described how pesticides contaminate both fog and soil swept off farm fields by wind and water erosion.

It is also tragic that fish, an excellent source of protein, B vitamins, and trace minerals that is low in saturated fat and high in good-for-your-heart omega-3 fatty acids, has too frequently been contaminated by pesticides and other pollutants. Although banned in 1972, DDT, a probable carcinogen in humans, and its byproducts are still frequently detected in fish, as is chlordane, widely used to control termites. Low-fat species caught far off shore, such as cod and haddock, tend to have the lowest levels of such chemical contaminants.

Toward Organic

Where have the official protectors of the nation’s natural resources been while all this has been going on? Agencies like the Soil Conservation Service have focused on soil erosion and related resource problems. But they have avoided getting into the pesticide controversy or challenging farm chemical use. The first official admission that something could be done about the impact of chemical fertilizers and pesticides on the environment came in a report on organic farming published in 1980 by a team of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists.

“Organic farming is a production system which avoids or largely excludes the use of synthetically compounded fertilizers, pesticides, growth regulators and livestock feed additives,” they reported. “To the maximum extent feasible, organic farming systems rely upon crop rotations, crop residues, animal manures, legumes, green manures, off-farm organic wastes, mechanical cultivation, mineral-bearing rocks, and aspects of biological pest control to maintain soil productivity and tilth, to supply plant nutrients, and to control insects, weeds, and other pests.”

The report concluded that organic farming is energy-efficient, resource-conserving, environmentally sound and productive, and that its adoption would help protect the environment. You would think environmentalists would have lined up in droves behind a report that contained so much good news. And that consumers would have rushed out to find food grown without chemicals. That kind of response never materialized.

Shortly after the report was published, the incoming Reagan Administration closed the USDA office that sponsored the report and fired the person who coordinated the study team work.

But the USDA report did set the stage for a 1985 Farm Act provision authorizing research and education on alternative farming systems. Legislators in more than 20 states passed laws authorizing state organic programs. Support also began building for national organic standards.

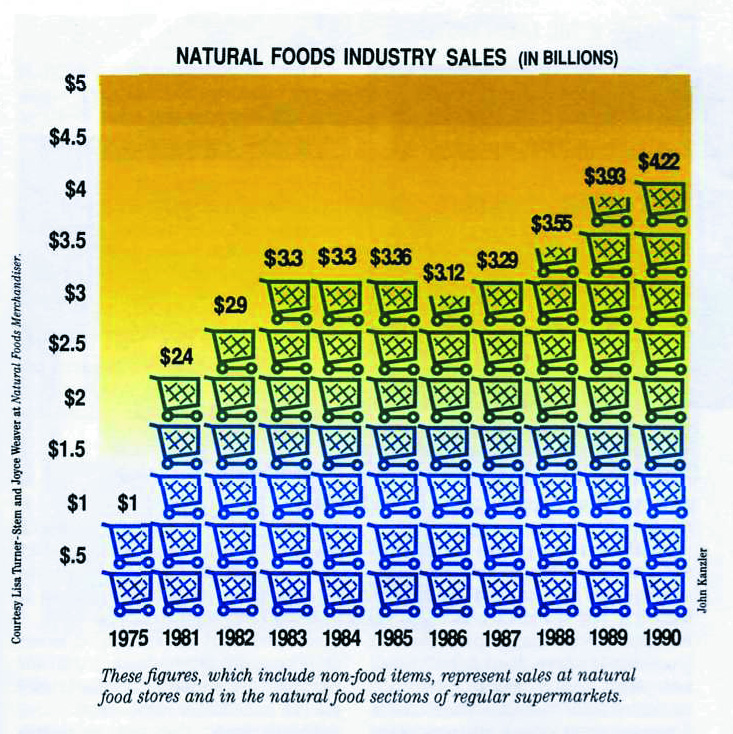

Consumer demand for food grown without chemicals also began to build. The first comprehensive report on organic food marketing in 1989 showed total sales of about $1.35 billion with anticipated long-term growth of 35 percent per year. Much of the increase in organic food sales came in food co-op and health food stores. A Natural Foods Merchandiser survey in 1989 showed sales in the natural foods industry were approaching $4 billion a year.

The trend toward eating with the environment in mind has been strengthened by consumer alarm over pesticide residues. This anxiety about chemical residues in food was dramatized in 1989 by a public uproar (spurred on by a 60 Minutes expose) over Alar, a potentially carcinogenic chemical used to hasten the ripening of apples. The ensuing publicity over Alar energized consumer advocates and drove the chemical off the market.

Rosalie Ziomek of Evanston, Illinois, one of those alarmed, and energized, was joined by other mothers with small children in setting up the Illinois Safe Food Coalition. It has become a highly visible opponent of farm chemical use and proponent of consumer activism and organic and sustainable agriculture initiatives. The Coalition recently proposed a national law that would mandate that all produce be labeled to show every pesticide used to produce it.

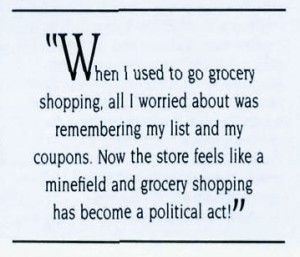

Ziomek makes her food purchase decisions on the basis of their impact on her family’s health and on the environment. “When I used to go grocery shopping, all I worried about was remembering my list and my coupons,” she recalls. “Now the store feels like a minefield and grocery shopping has become a political act!”

The food safety concerns that spurred the Illinois Coalition and many others like it are reflected in polls that show consumers are increasingly interested in buying food produced in a way that protects both consumer and grower health and the environment. The latest survey by The Packer, the trade publication of the produce industry, showed that 46 percent of the respondents said they were more concerned about chemical residues than a year earlier and that 26 percent had changed their food buying habits because of chemical residues. Changes included buying organic or locally grown food, or food marketed with a “no detectable residue” label.

The food safety concerns that spurred the Illinois Coalition and many others like it are reflected in polls that show consumers are increasingly interested in buying food produced in a way that protects both consumer and grower health and the environment. The latest survey by The Packer, the trade publication of the produce industry, showed that 46 percent of the respondents said they were more concerned about chemical residues than a year earlier and that 26 percent had changed their food buying habits because of chemical residues. Changes included buying organic or locally grown food, or food marketed with a “no detectable residue” label.

Since the Alar episode, residue-testing services have been available to supermarkets from several new enterprises. Supermarkets that employ companies such as the California-based NutriClean identify produce with shelf tags or advertisements as certified to be free of “detectable” chemical residues. But a lack of “detectable” chemical residues doesn’t fully address food safety or environmental concerns. It reflects only a small aspect of growing food in an environmentally responsible way. It does not assure that the food was grown without farm chemicals or with methods that conserve and enhance the quality of soil, water and energy resources. All these factors, in addition to pesticide use, are considered in setting organic standards.

National polls also show strong support for organically grown food that is sold with a label backed up by third-party certification. National organic standards that take effect in 1993 will provide assurance that food labeled as “organically grown” is produced with inputs and methods that do not pose a health risk or harm the environment.

Diet-Health-Environment Connection

The diet-health connection established in the 1980s is evolving in the 1990s into a diet-health-environment connection, with strong consumer interest in healthful food that is Earth- , friendly as well. Eating with the environment in mind can go hand-in-hand with following expert advice on eating more healthfully.

The expert advice about cholesterol and animal fat seems to have sunk in: Per capita consumption of red meat (which includes beef, pork and veal) is at its lowest levels since the early 1960s; egg consumption has declined steadily since the end of World War II, and there has been a steady switch from whole milk to nonfat and skim. The proof isn’t in the pudding, though. It’s in the fact that the number of Americans dying of heart disease has dropped about 30 percent since 1978, due in part to diet and in part to a decrease in smoking.

And, according to Alan Durning of the Worldwatch Institute, declining red meat consumption also is good news for the environment. The bad news that goes with it, according to Durning, is that total meat consumption is increasing, as consumers switch from red meat to poultry.

“Regardless of animal type, modern meat production involves intensive use—and often misuse–of grain crops, water resources, energy, and grazing areas,” Durning says. “In addition, animal agriculture produces surprisingly large amounts of air and water pollution. Taken as a whole, livestock rearing is the most ecologically damaging part of American agriculture.”

Fred Kirschenmann, who manages a 3,100-acre organic farm in North Dakota that includes grassland and a beef herd, doesn’t quite agree. “Ninety percent of what our beef cattle consume cannot be utilized in any other way. This includes grass, straw and grain screenings (chaff and seeds),” he reports. “In addition, about 40 percent of the fertilizer required to produce our crops comes from livestock manure.”

Kirschenmann says that the questionable practices in animal production, such as huge beef feedlots and confinement feeding in hog and chicken factories, are the result of separating crop and livestock production into specialized units. “Animals and plants always appear together in natural systems,” he notes. “The challenge is to re-integrate animals into agricultural production systems.”

A new USDA report backs up Kirschenmann’s statements about livestock utilization of straw, grass and other feed that cannot be used for food. The report shows that two-thirds of all agricultural land is in pasture and rangeland that accounts for 38 percent of total tonnage of food consumed. “Most of the area pastured is land that cannot be cropped,” the report adds. “Livestock enable this land to make a significant contribution to the food supply.”

Durning agrees that “there is nothing anti-ecological about cows, chickens and pigs themselves. Rather, American-style animal farms burden nature because they have outgrown their niche.”

Think Globally, Eat Locally

But eating fewer fatty foods like meat is only part of the prescription for health and environmental protection. Eating fresh, unprocessed fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is the best thing you can do to lower your risk of several types of cancer and heart disease. Buying locally or organically grown fresh fruits and vegetables may also be the best food choice you can make for the environment.

Locally grown does not necessarily mean produced without harmful chemicals. It does mean, in almost every case, that no post-harvest pesticides have been applied. More important, it means food has not been shipped in by truck, rail or air from far away. The savings in fossil fuel energy is an indirect, but no less important, benefit to the environment.

Buying locally grown produce encourages “seasonal” eating and discourages consumption of fruits and vegetables shipped long distances, often from the Caribbean and South America, and long-term storage in low-temperature facilities. Both are enormously wasteful of energy and add indirectly to the American appetite for fossil fuel energy. Supermarkets commonly bring in produce from hundreds of miles away even when it is, or could be, grown locally.

With so many deceptive and misleading claims appearing on food labels and advertisements, it’s extremely difficult to sort out all these messages about diet and health and the environment. Take pork, for example. That industry has spent millions of dollars each year trying to dupe consumers into thinking pork is as healthful as chicken, turkey, and fish by advertising pork as “the other white meat.” However, USDA data show that almost all cuts of pork are considerably higher in fat, saturated fat and calories, and the “other white meat” ad campaign is currently under investigation by the Federal Trade Commission. True, pork tenderloin is lean, but only two or three percent of pork bought in this country is pork tenderloin.

Alan Durning, in a WorldWatch Report, singles out pork as the most ecologically damaging meat you can eat. Pound for pound, he reports, pork plunders more resources than beef, chicken, eggs or milk; it takes more grain, more energy and more water to produce, and more energy to supply it to consumers. (Unlike cows, pigs feed solely on grains and are less efficient at converting food to muscle).

The Nutrition Education and Labeling Act passed last year was designed to help consumers sort all this out. Labels will have to list total calories and calories from fat in a typical serving, the amounts of total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and other information. The bad news is that the law only applies to food regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This means that meat, poultry, and meat products, which are regulated by USDA—and which are some of the fattiest foods we eat—won’t be covered.

American consumers appear less concerned about how their food is grown and its impact on the environment than Europeans. A growing number of German consumers, for example, are choosing “conclusive products” in food markets. This term identifies food produced with environmentally sound and socially acceptable growing, processing and packaging and, in some cases, storage methods.

Hardy Vogtmann, director of the Division of Alternative Agriculture Methods at the University of Kassel, discussed changes in buying habits among German consumers in a presentation at a recent international organic agriculture meeting.

“Previously, the motivation was simply to obtain healthy food; this has expanded into a more altruistic attitude wherein purchasing power supports production methods conducive to a healthy environment,” he reports. “A large proportion of consumers has become aware of the wider context of food production; to be acceptable food must be healthy and healthfully produced, not only for oneself, but for the environment and the larger society as well.”

The U.S. environmental movement, spurred on by 1990’s Earth Day observance, has hit the supermarkets in the form of a variety of “green” products and “Earth-friendly” brands. But, so far, most of the focus has been on the development of biodegradable products, products easily recycled, and on source reduction. Surely “green” foods cannot be far behind.

Can health and environmental enhancement be linked to agricultural production? A growing number of Americans think so. A recent study by Health Focus, a market research firm based in Emmaus, Pennsylvania, showed that consumers view organically grown food as safer to eat, safer for farmers, and safer for the environment.

We agree.

______________________________

LISA Y. LEFFERTS, MSPH, staff scientist at the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), is the Center’s expert on food safety and risk assessment. She recently co-authored Safe Food: Eating Wisely in a Risky World (Living Planet Press).

ROGER BLOBAUM is the director of Americans for Safe Food, a project of CSPI. He has served as editor of Alternative Agriculture News, and as managing editor 0f American Journal of Alternative Agriculture.